Speaking Engagements UPCOMING

Predict and Prepare sponsored by Workday 12/16

PAST BUT AVAILABLE FOR REPLAY

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #171, 2/15

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #160, 8/14

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #145, 1/14

Workday Predict and Prepare Webinar, 12/10/2013

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #134, 8/13

CXOTalk: Naomi Bloom, Nenshad Bardoliwalla, and Michael Krigsman, 3/15/2013

Drive Thru HR, 12/17/12

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #110, 8/12

Webinar Sponsored by Workday: "Follow the Yellow Brick Road to Business Value," 5/3/12 Audio/Whitepaper

Webinar Sponsored by Workday: "Predict and Prepare," 12/7/11

HR Happy Hour - Episode 118 - 'Work and the Future of Work', 9/23/11

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #87, 9/11

Keynote, Connections Ultimate Partner Forum, 3/9-12/11

"Convergence in Bloom" Webcast and accompanying white paper, sponsored by ADP, 9/21/10

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #63, 9/10

Keynote for Workforce Management's first ever virtual HR technology conference, 6/8/10

Knowledge Infusion Webinar, 6/3/10

Webinar Sponsored by Workday: "Predict and Prepare," 12/8/09

Webinar Sponsored by Workday: "Preparing to Lead the Recovery," 11/19/09 Audio/Powerpoint

"Enterprise unplugged: Riffing on failure and performance," a Michael Krigsman podcast 11/9/09

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #39, 10/09

Workday SOR Webinar, 8/25/09

The Bill Kutik Radio Show® #15, 10/08

PAST BUT NO REPLAY AVAILABLE

Keynote, HR Tech Europe, Amsterdam, 10/25-26/12

Master Panel, HR Technology, Chicago, 10/9/012

Keynote, Workforce Magazine HR Tech Week, 6/6/12

Webcast Sponsored by Workday: "Building a Solid Business Case for HR Technology Change," 5/31/12

Keynote, Saba Global Summit, Miami, 3/19-22/12

Workday Rising, Las Vegas, 10/24-27/11

HR Technology, Las Vegas 10/3-5/11

HR Florida, Orlando 8/29-31/11

Boussias Communications HR Effectiveness Forum, Athens, Greece 6/16-17/11

HR Demo Show, Las Vegas 5/24-26/11

Workday Rising, 10/11/10

HRO Summit, 10/22/09

HR Technology, Keynote and Panel, 10/2/09

Adventures of Bloom & Wallace

|

A Page From Bloom’s Camera 1950 Catalog Ron left the house this morning before dawn, headed to Redmond, OR to spend Christmas with a range of Wallaces. Time moves more slowly when I’m alone, and it’s a very rare treat. Having a few days at home completely on my own hasn’t happened in years, in part because Ron was reluctant to leave me — and I was reluctant to be on my own — as my mobility problems grew worse, but I’m doing well enough now that he was able to go with a clear mind. And I so needed this time alone. I’ve got a lot to do, and it will get done, but it’s much more than that.

I’ve always been someone who needed time alone with her own thoughts, a very independent someone who has struggled with every bit of lost independence as my legs, really my whole body, fulfilled the diagnosis, staved off with real effort for several decades, that I had received in my late 30’s. I’m so very grateful for the many extra years of good health I’ve enjoyed, for all that having a strong body has allowed me to do, and I’m determined to keep fighting the good fight. But having a few days in which I decide when/if I want to do something without taking someone else’s needs/wants/schedule/etc. into consideration makes me feel young again, and it’s been far too long since I’ve had the freedom to do that.

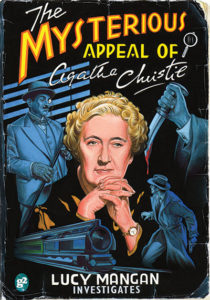

I’ll get back to writing about my life after a career in HR tech on Tuesday, about the murders I’m encountering along the way (as in murder mysteries), and about my increasingly portfolio life style. But first, let’s celebrate Christmas, a holiday which always takes me back to my childhood in the 1950’s for reasons which will become obvious. The memories of those early years become more vivid rather than less so with the passage of time. I can still taste the special foods prepared for each Jewish holiday, still remember the excitement of packing carefully labeled uniforms for each summer’s two months at Camp Mar-Lin, and still remember Bubbi Bloom’s incredibly sage and still applicable advice better than I can remember what I ate for lunch yesterday. Aging hasn’t dimmed my memories; au contraire, it has sharpened up the important ones and blurred the trivial.

My education as a business woman began almost at birth. I learned so much about business, absorbed it through my pores, as I worked at Bloom’s Camera (later, Bloom’s Photo Supply and then just Bloom’s, Inc.), lingered at my grandmother’s kitchen table after Friday night Shabbat meals where all the important decisions were made for that business, and was then apprenticed to all the other small businesses run by various relatives. I went on buying trips to New York for the fancy ladies wear shop run by one aunt (they used to model the dresses at high end shops), learned the uniform business from another aunt, and was taught the basics of the Borscht Belt hospitality business by a great cousin. By the time I got to my MBA program, cash flow, supply chain, human resource management and more were already baked into my world view. So, with Christmas almost here, I thought you might enjoy a retail merchant’s Jewish child’s perspective on this holiday.

Bloom’s Photo Supply — The Great Wall On Christmas Eve, my Dad’s retail camera shop closed early, and we knew we’d have him with us all that next day. Really just with us, even if he were too tired for much conversation after working the very long hours of the retail Christmas season. New Year’s Day was for taking inventory, and it was all hands, even my very small hands, to the wheel. But Christmas Eve and Christmas Day were really special.

Time alone with my father (of blessed memory) Jack Bloom was rare and precious. He ran a modest camera shop with his two brothers, Paul (who passed away in early January, 2015, just after his 99th birthday and who has entrusted me with finishing his memoir), and Herman (who also published several “romantic” novels under the name Harmon Bellamy). Our cousin Elliot took over the family business as our fathers retired (he was our only male Bloom cousin so he was always the heir apparent), automated early and aggressively, built it up into several thriving divisions, and then sold at the absolute peak. Well done Elliot!

When I was really young, my Dad left for work before dawn and rarely got home before I was put to bed. Friday nights were usually spent having Shabbat dinner, with all my Bloom aunts/uncles/cousins and even great aunts/uncles (those without their own children), at my grandmother’s house. After dinner, Dad went off to Schul with his brothers. On Saturday mornings, we were all off to Schul, but we were orthodox so my only male first cousin, Elliot got to sit with his Dad. The store was open on Saturdays, so my Dad and his brothers, despite the Orthodox prohibition against working on Shabbat, went from schul to work on many Saturdays, especially if they were short-handed by employee illness or vacations. Summer Sundays were for golf in the mornings and family time in the afternoons, often spent visiting family who lived far away. For example, in those turnpike (yes, before there were highways, there were turnpikes) days, the trip to Hartford, less than thirty miles away, took well over an hour.

But on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day, we didn’t go visiting. After working extra long hours during the run-up to Christmas, we stayed home so that Dad could rest. That meant me sitting beside him as we watched TV (once we had one) or read from the World Book Encyclopedia. My Dad was a great reader, something my sister and I have “inherited” from him, and every Jewish home in those days purchased an encyclopedia, volume by volume, convinced this was essential to their children’s education.

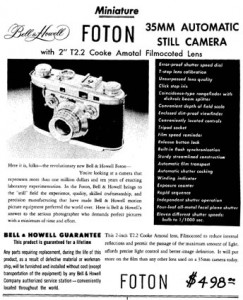

With everyone, including the mothers, working long hours, it was rare to see my Dad during December except when I was working at the store. My cousin Ronni (of blessed memory) and I, from about age seven, ran the strange machine in the open mezzanine above the retail floor that took addresses on metal plates and transferred them to labels for the Christmas mailing of catalogues (like the one pictured above) and calendars. Long before it was fashionable for small businesses, Bloom’s Photo Supply was into direct marketing, and we carefully collected the names and addresses of every customer and caller, all of which were entered in the perpetual address files that my Uncle Herman kept.

Sitting in the mezzanine, Ronni and I bickered over whose turn it was to load the metal plate (not fun), load the next item to be addressed (not bad), or turn the wheel (most fun) and discussed what we saw going on all around us. Excess inventory, the bane of every retailer then and now, was a major topic, along with fanciful ways of getting rid of it profitably. We also took careful note of anyone who appeared to be shoplifting, quickly reporting any irregularities with arranged signals to the salespeople on the floor, and our eyes and instincts were sharpened by those experiences. Even today, on the rare occasions when I’m in a store, I can’t help but notice such behaviors.

While I can never be sure, I think those conversations with Ronni must have been the origin of my now famous story about the invention of Christmas as an inventory management scheme. In that story, first told publicly in its entirely to my Wallace family when joining them for our first Christmas as a married couple, the wise men were retail merchants who saw in the humble birth of Mary and Joseph’s son a solution to the already age-old problem faced by retailers everywhere of how to ensure that the year ended without extraneous, highly unprofitable inventory. This is one interpretation of the Christmas story that my Christian Wallace family had never heard until they met me.

By the time we were ten, Christmas season found Ronni and me, the two youngest Bloom cousins, helping behind the counter after school and on weekends, ringing up sales, selling film and other simple products, dealing with shop-lifters rather than just watching for them from afar, recording those sales in the perpetual inventory files kept by my Uncle Herman (there never was nor ever will be again a filer like my Uncle Herman!), and generally learning the business. Everyone worked during the month before Christmas, including our mothers who were otherwise traditional homemakers, and by Christmas Eve, we were all exhausted. But the lifeblood of retail is the Christmas shopping season — always was so and still is — so our family budget for the next year was written by the ringing of those Christmas cash registers. Throughout my career, whenever I agreed to a client project or speaking engagement, I could still hear, ever so faintly, that old-fashioned cash register ka-ching.

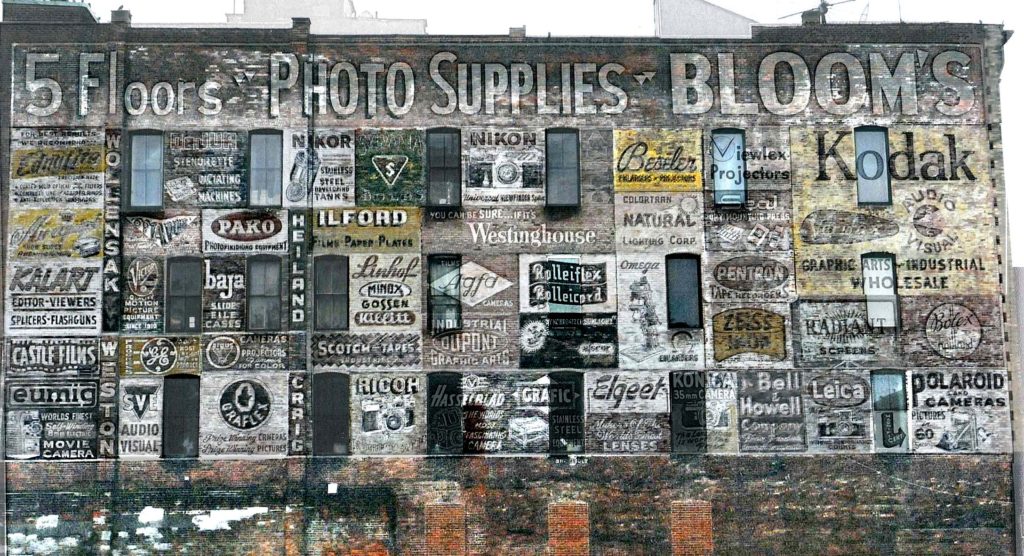

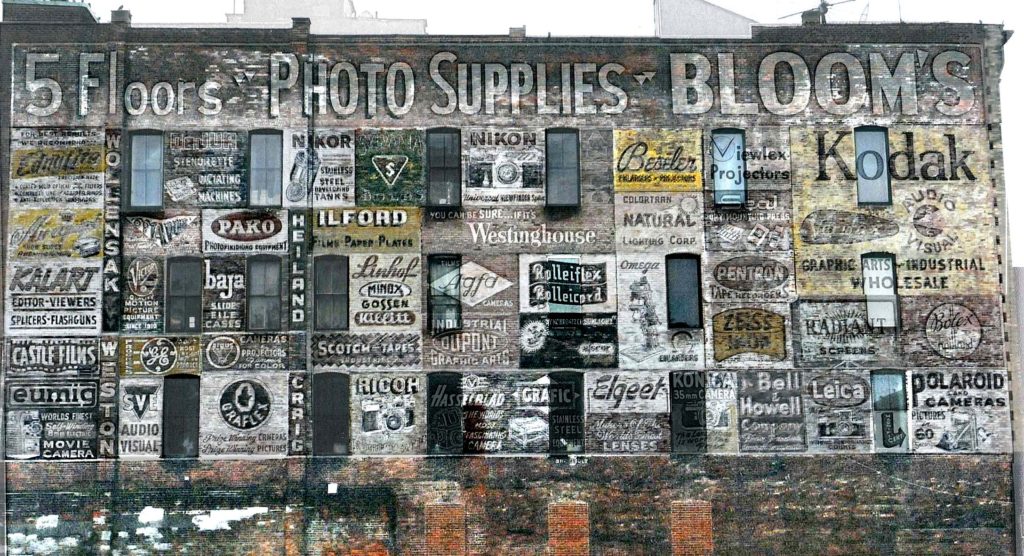

My Dad was buried on my 50th birthday. My cousin Ronni, just four months younger than me, died in her mid-thirties. Cousin Elliot, Ronni’s older brother, took over the business from our fathers when they retired, built it into something completely non-retail but VERY successful, and sold it 15+ years ago. But if you’re ever in Springfield MA, you can still see the four story mural of long gone camera and photographic supply brands on the exposed wall of Bloom’s Photo Supply’s last retail address, on Worthington Street, just up from Main Street.

For me, sitting in my usual place at the keyboard, Christmas Eve will always be special. Years after my Dad retired and I had a business of my own, we talked daily, with me updating him on my business in response to his questions. You can’t fail to hear the ghosts of a retailer’s Christmas past even as my very non-retail business thrived. ”How’s business?” “Business is great Dad.” “Are your clients paying on time? “They sure are, Dad.” “And are their checks clearing the bank?” “Absolutely.” This Christmas Eve, I’d give every one of those checks for another Christmas with my Dad.

To all my family, friends and colleagues who celebrate the holy day of Christmas, may you and yours enjoy a wonderful sense of renewal as you celebrate the great miracle of Christ’s birth. And please pray hard, on behalf of all mankind, for more peace on earth in 2018 than we’ve had in 2017.

Take Your Chances, Win Some Gelt Chanukah 2017, With My HR Tech Wishes For 2018

Have you ever played the Chanukah game of spin the dreidel? With or without the modified rules derived from “spin the bottle?” Did you know that the four letters, one on each side of the dreidel, make up a phrase that translates to “a great miracle happened here.”

Chanukah celebrates the miracle of freedom, a celebration not of a military victory (although there was a pretty big deal victory associated with the holiday) but rather of the miracle of G-d’s attention to the details of everyday life. With the Temple destroyed, the Jewish fighters, who had retaken the Temple and cleansed it of the idols with which the conquerors had desecrated the Temple, found only a little oil with which to light the eternal flame which burns in front of every Ark of the Torah to this day. While a runner was sent to the nearest source of holy oil, expected to take eight days roundtrip, the eternal flame was lit with what little oil could be found. It’s because that little bit of oil kept the eternal flame lit for the eight days needed to secure a new supply that we celebrate Chanukah for eight days. Yes, there was a big military victory, but that’s not what we celebrate. Instead, we celebrate the fact that, having done all that we could to keep our commitments to our faith, G-d did the rest.

The celebration of Christmas often falls in the same period of the Gregorian calendar as does Chanukah. And we Jews may have added and then expanded the tradition of gift-giving on Chanukah rather than listen to the cries of disappointed Jewish children drowning in Christmas marketing. And although these two holidays are quite different in their origins and application to modern life, both of them celebrate the fact that a great miracle happened here, where here is in Bethlehem for Christmas and in Jerusalem for Chanukah. One of the things which surprised me the most on our first trip to Israel was how very close together are the great biblical landmarks of both faiths.

So, in the spirit of this miraculous season, here are the 2018 “miracles” — and I use that word intentionally because I think it would take divine intervention to achieve them — I so wish to see in our neighborhood, at the intersection of IT and HRM:

- The end of marketing speak in our industry, of calling everything you’ve got AI or ML or VR or IoT or cloud or social or integrated or predictive analytics or automagical etc. Can you just imagine how much easier it would be for buyers and customers if there were no more “painting the roses red?”

- The end of chest beating by industry executives, of hyping their own accomplishments in hopes no one will ask too many questions, and of disrespecting the competition in loud voices and with known half-truths if not outright lies. Do these folks realize how much they sound like a certain President?Prospects and customers would much prefer that their vendor executives tout their customers’ accomplishments and customer satisfaction scores.

- The end of whatever atmospherics discourage so many young women from aspiring to be and then becoming chief architects, heads of development and CTOs. I know the barriers intervene minutes after birth, and our industry can’t fix all of them. However, our HR leaders can do everything in their power to level the recruitment, development and advancement playing field and to ensure that the organizational culture is welcoming to women in tech roles. As for what our IT leaders can do to help, they can make their work groups gender-neutral in every respect, from the jokes and anecdotes they tell to the respect they show for differences in styles of communication and engagement. And yes, this is of particular importance not only to me personally but to every employer who can’t afford to waste half of the scarcest competencies.

- The end of bad HRM object models. We know how to do this right, or at least some of us do, and it’s way past time that the mistakes of the past were relegated to that past. I can’t tell you how frustrating it is for me to review relatively new HRM software whose designers haven’t bothered to study the sins of HRM software past. Even if you have a gorgeous, easy to use, and truly efficient UX, we can’t do succession planning without the granularity of position, and we can’t do talent management without a robust, multi-dimensional understanding of knowledge, skills, abilities, and all other work-related capabilities.

- The end of bad HRM enterprise software architectures. For example, how could anyone design true HRM SaaS that doesn’t provide for cross-tenant inheritance (e.g. so that you can embed and maintain a single set of prescriptive analytics, with their content and advisory material, then inherit it across all relevant tenants — i.e. those which have signed up for this service — with appropriate modifications by geography done once and then used to modify, by geography, that decision tree of inheritance)? And how could anyone design true HRM SaaS which doesn’t express all of its business rules, from workflows to calculations, via effective-dated metadata? And, what’s even more frightening, there are folks developing HRM enterprise software who aren’t even thinking about these issues.

- The end of bad HRM enterprise software development methods. I’ve been a strong proponent of definitional, models-based development since the late 80’s. My commitment to writing less code goes back even further. So it’s little wonder that I’m stunned when I hear enterprise software execs calling attention to their thousands of programmers when they might be able to accomplish even more with fewer developers and better development methods.

I could go on, but I think you get the picture. It would really be a miracle if we woke up on the last day of Chanukah to find that all of these wishes had come true. But even more important, although it has absolutely nothing to do with HRM or IT, I hope that the miracles of good health (mental, physical, and financial) are granted to each and every one of you. And may the lights of Chanukah break through the darkness that threatens the very roots of our democracy and be a beacon of hope for all mankind in 2018.

[This should have been written and published in early March, but that’s when our kitchen remodel project went into what’s called demolition, and life at Bloom & Wallace has been pretty disrupted ever since. It’s going to be gorgeous when finished, but first we have to survive the process. And I can tell you from experience that designing and building from scratch, with us living thousands of miles away and only being onsite once a month, was less stressful than having our home turned into a construction site while we continue to live (or, as Ron says, camp) here. But that’s a topic for a series of posts, of which this is the first one.] [This should have been written and published in early March, but that’s when our kitchen remodel project went into what’s called demolition, and life at Bloom & Wallace has been pretty disrupted ever since. It’s going to be gorgeous when finished, but first we have to survive the process. And I can tell you from experience that designing and building from scratch, with us living thousands of miles away and only being onsite once a month, was less stressful than having our home turned into a construction site while we continue to live (or, as Ron says, camp) here. But that’s a topic for a series of posts, of which this is the first one.]

I really enjoy listening to the best of our industry’s earnings calls. Putting aside the detailed financial discussions, which aren’t my primary focus but may be yours, I learn a ton from the vendor’s executive commentary, and from the personal style of the presenters, about what’s actually going on in these firms and within their competitive landscape. I also learn a ton from the questions of the financial analysts, the answers vendors execs give, and from what’s neither asked nor answered.

Workday’s latest earnings call, on 2-27-2017, caught my attention primarily because of what the financial analysts didn’t ask. I was ready for some very specific questions about one initiative which goes to the heart of Workday’s ability to onboard customers better/faster/cheaper and to provide similar ongoing support throughout the continuous implementation which is foundational to achieving SaaS’s innovation benefits. I was also ready for questions about another initiative which goes to the heart of expanding Workday’s addressable market “bigly.” Well, I may have been ready, but either the financial analysts didn’t think this was the right moment for such questions and/or their interests are WAY different from mine. Neither initiative was mentioned, not by Workday and not by the analysts, and so begins my tale.

At Workday Rising 2016’s Financial Analyst program, to a standing room only crowd (well, to be fair, the financial analysts all had seats, but there were definitely some Workday folks without them), Workday did a presentation on what I have long called interrogatory configuration. Here’s a more recent commentary on this topic. Just think of interrogatory configuration as the complete set of tools which speed up, systematize, and wring elapsed time, cost and errors out of the nearly continuous implementation which is a hallmark of true SaaS’ ability to support today’s rapid pace of business change by improving our ability to take up both new capabilities and reconfigure existing ones. Workday had made real progress in this area and did a solid presentation on their goals here and progress toward those goals. I kept waiting for one or more of the analysts present to jump on their chairs, scream eureka, and then, more calmly, ask a bunch of probing questions about the what, why, how, when, etc. Instead, you could have heard crickets!

Then, toward the end of that same Financial Analyst program, in answer to the always asked (and on earnings calls too) question about whether or not Workday was going to commercialize their development platform/environment, I awaited Aneel’s carefully expressed view that this would be a different business and one which would distract Workday from their current applications and, more recently, industry build-out. Instead, the earth moved (at least for me) when Aneel casually stated that they would be commercializing their crown jewels and, wait for it, by the end of 2018. I nearly fell off my chair over such a public revelation of so important a development as a kind of throwaway line at the end of the day. Perhaps by then the analysts were too pooped to participate, but there were few questions and even fewer sidebar conversations — and I was listening for both of them.

Meanwhile, I’m sitting in that session trying to calculate in my head the financial implications for Workday (not to mention the even bigger list of hard benefits, to include both cost savings and more rapid uptake of innovation, for their customers) from interrogatory configuration, e.g. improvements in operating margins, from materially lowering the time and cost to initial production, and the greatly expanded addressable market from unleashing their platform/development environment not to mention the related bragging rights and overcoming what some competitors (and industry analysts) have cited as a Workday weakness. And while there were some mentions in financial analyst reports of the day of what I considered pretty momentous announcements, there wasn’t anywhere near the excitement that I had expected. But of course such matters take time to digest, to probe more deeply through partner and customer reality checks, etc. — hence my expectation of nuanced questions on these initiatives at the February earnings call.

Little wonder then that I was so surprised when there wasn’t a peep about either of what I consider to be two important levers of Workday’s future addressable market and profitability, but what do I know? Not one peep! But I’m sure that Workday’s implementation partners are following both developments with great interest, the one because it could reduce sharply their implementation workload — really, everyone’s workload — and the related revenue streams, and the other because it could empower partners to build-out Workday where they have deep subject matter and/or industry expertise.

Of course I don’t have access to every financial analyst report covering Workday and her competitors, nor do I read every industry analyst report on this same competitive landscape, so I may well have missed some fantastically insightful coverage of these initiatives. If I have, please, please send those to me. Meanwhile, I’ll await coverage of Workday’s upcoming Tech Summit (I really hate to miss this, but cruising the Western Med intervened), their next earnings call, and then Workday Rising in hopes of learning more.

At the end of 2009, as the ACA was being born, while I was recovering from a fully insured (but dreadfully painful post-op) rotator cuff surgery, I shared my two cents worth on the coming of the ACA. With the healthcare debate now front and central in the GOP-controlled Congress, which is committed to repealing the ACA but with no coherent replacement plan in sight, I thought it was time to review this topic. And yes, Ron and I remain fully covered by Medicare and a terrific supplemental policy through his previous work for and retirement from NASA.

If we’re serious about having high quality and solid health care coverage at affordable prices for every American who isn’t covered by an employer-provided plan (but with those plans required to provide the same solid coverage as their baseline), by Medicaid or Medicare, then it’s clear that we’ve got to make peace with some foundational principles. Telling someone that they can buy any policy they want when they can’t afford either the policy premiums or the associated fees and co-pays isn’t very helpful. Nor is ignoring the reality that timely access to preventive, diagnostic, and curative healthcare is truly a matter of life and death — deaths which will be on all of our hands if we don’t figure this out. So here’s what I’ve been thinking about all of this.

First, we’ve got to reform our health care system itself to get out as much waste and corruption as possible so that no one, whether provider or insurer or pharma etc., is making an obscene profit and that everyone involved is being taxed progressively. We need incentives for tackling and triumphing over the most costly health care issues, prevention built into our culture and our medical delivery, and the expectation that we’ll all get good basic coverage while the rich are free to pay as they choose for the extras. Funding high costs targets, like cancer and Alzheimers, where cures or prevention would have a huge impact on overall health care costs must be a top priority.

Second, we need everyone to participate, with the costs shared equitably and progressively. Yes, men may not need pre-natal care, and women may not need prostrate care, but we’re all in this together when it comes to improving the health and reducing the suffering of our family/friends/communities so policies must be gender neutral in their coverage to ensure that we’re all in this together. As to costs being shared equitably and progressively, those with the least will be subsidized, those able to pay will do so on a sliding scale so that those with the most do in fact subsidize those with the least. Having a healthy community matters to the wealthy as much as it matters to everyone else, and getting everyone vaccinated for the flu helps ensure that the wealthy stay healthy. So, no more fussing from those at the top because they’re asked to pay more, and no more fussing from anyone over the requirement that they get certain preventive and wellness care.

Third, there’s a ton of profit sloshing around in our current healthcare system, but we Americans are inclined to keep a private sector approach to healthcare. As long as we accept that every bit of that profit will be honestly earned and that those who try to profit dishonestly will be nailed and jailed, I’m inclined to continue our efforts to make an essentially for profit healthcare system work. But that means doctors must be prepared to shut down the bad doctors, hospitals must be prepared to police their own, big pharma must accept some degree of cost control and price negotiation, and the list goes on. There’s simply no way to achieve a private sector health care world that serves all of us well unless the bad actors are removed.

Fourth, we need to automate the hell out of every aspect of our healthcare system and do it intelligently. We clearly need a master healthcare record that’s complete, portable, and owned by the patient. Started at birth, this record should travel our preventive healthcare, from vaccinations and other preventive measures to wellness-related activities, our healthcare issues/diagnoses/treatments/etc., and all tests, doctors visits, hospitalizations, etc. But a universal healthcare record isn’t nearly enough. When doctor’s write prescriptions, they should be advised right then about generics, costs, drug interactions, needed instructions to patients, everything. Same with any recommended tests and procedures. Doctors make mistakes, overlook things in those huge manual files upon which so many of them still rely, and almost never have any idea about costs. Technology can do a lot here to reduce mistakes, improve care and reduce costs, but it would take the level of cooperation across the healthcare system that we see across the payments system.

Finally, every single one of us — and this means me no matter how uncomfortable the reality — must be ready to walk, eat healthy, get our wellness checkups, vaccinate our children, stop smoking, treat our addictions forcefully, and do all the other things which improve our individual and community health. We must get back to a set of values which limited risky behaviors because those who practiced them were shamed — yes, shamed — into changing their behavior. Opioid addiction takes both supply and demand, and the sooner we start jailing the overprescribing physicians the better. Vehicular accidents where speeding or DUI are involved are a choice by the driver, and those drivers should also be nailed and jailed. And those who want to play extreme sports or otherwise gamble with their health should do so at their own risk and without the expectation that the collective healthcare system is going to take care of them. Just as drivers of certain vehicles pay much higher insurance rates, so should partakers of other risky lifestyle activities. Fair’s fair.

Yes, we can do this. But first we need to have the conversation about the principles upon which our healthcare system is going to be based. I’m sure no one will agree with mine, but we have to start somewhere to decide what we want our healthcare system to look like when we grow up.

Strategic planning is a mindset which can be applied to great swaths of your life. If you’re willing to do the heavy lifting, just like in business, strategic planning provides much improved outcomes.

With all of my exciting plans for Christmas and New Year’s taking a back seat to my second head/chest cold of the season — or, as the Queen’s own was described, my heavy cold — I’ve had some rare down time to do a little thinking about life, the universe and everything. Thinking really takes time, quality time, time which isn’t time-shared with anything more distracting than swimming laps.

I tend not to write about stuff until I’ve had a chance to let new ideas soak in and/or seen how older ideas have stood the test of time and are worthy reprising or refactoring. But one idea that’s been screaming for a post is the notion that the very methodology I developed for strategic HRM and HR delivery systems planning with a focus on improving organization outcomes is a perfectly good methodology for thinking about how to improve the outcomes of your life. Or perhaps my personal life planning approach came first and just morphed into an important part of my professional repertoire.

But whether chicken or egg, what’s important is that we approach all of life with an outcomes-based mindset, one which allows for serendipity, for mazel, but which doesn’t rely on it. If you’re interested in thinking strategically at every stage of life about how best to achieve your major goals, here are some of the key questions to ask yourself:

- What am I trying to accomplish? What are the outcomes I want to achieve?

- How am I doing toward those goals? What specific actions am I taking in order to achieve those outcomes?

- What are the barriers, if any, toward achieving those goals? What (and who!) stands in the path between me and the outcomes I desire and how such each of these impede my progress?

- What could I do, what resources could I draw on, and/or what help could I get to remove those barriers and move toward my goals? And when those barriers are people, how can I either change their behavior to be at least a neutral influence on achieving my outcomes or remove them entirely from my life (but of course without doing them any serious harm)?

- What would help me achieve my own goals more fully, more quickly, with fewer resources, and/or with less pain and suffering? Are there better ways to achieve my desired outcomes? How might I enlarge the solution space (aka think outside the box) in order to find better tactics?

Do you think this way naturally about every aspect of your life? Few people, including me, do so, but it is possible to train our brains to be analytical, to think critically, and to reflect carefully on how to get from where we are to where we want to be. Of one thing you can be sure: without exception, if you don’t know where you’re going, if you haven’t set goals quite firmly, then you sure as hell won’t know when you’ve achieved them and, even worse, you may waste your life wandering around without having accomplished anything. Even worse would be to have very clear goals which you never achieve, in spite of working your little heart out, because you haven’t got a clue on how to get from here to there.

Preface

I don’t know what got into me. Without any planning of plot or characters, without any outline of key points chapter by chapter and, quite frankly, without knowing what the hell I was doing, I just started writing. The first chapter was posted 12-6-2016 (the finale on 12-30-2016), and then the fat really was in the fire. Except for our annual holiday letters to friends and family, field reports of our travels, a few blog posts about holiday traditions, and similar, I haven’t written anything in half a century that wasn’t about enterprise technology, especially HR technology, or a required paper for my MBA. And just because you’ve read at least fifty “Golden Age” (in style or actuality) mysteries per year during all of that time, it doesn’t make you qualified to write your own. I’ve never written anything in all those years, except a grocery list or thank you note, which didn’t start with a clear purpose and outline. But this novella literally wrote itself, pouring out of me, chapter after chapter, in a mad dash to the finish line. It’s as though letting go of my career has freed up whole swaths of synapses and storage cells which are determined to find a new purpose. What they do next is going to be a surprise for both of us, hopefully a pleasant one.

In which we meet Zelda, Creepy and Doha Doha

It was a dark and stormy night at Metadata Hall, the restored country manor house which was the UK regional headquarters for Great Software Inc., one of the largest global providers of all the software that anyone should ever need. Most employees had long since left for the long Bank Holiday weekend, but Zelda Kahniefmeyer was hunched over her desk, with just the pool of light from the desk lamp keeping the night creatures at bay.

“What the hell am I going to do,” says our heroine, the development manager for Great Software’s next generation architecture, the skunk works and very stealthy project on which the company was betting its future. Tucked away in this bucolic corner of the UK, out of sight of the prying eyes of industry and financial analysts, Zelda’s mission was clear and urgent. But such was not the case with her HR partner, Creepy Cummins (really Daryl Cummins, but he was truly creepy). Creepy was neither clear as to what was needed people-wise to make this next gen effort, code named Metadata Hall, successful nor did he exhibit the slightest sense of urgency. But most counter-productive was creepy’s insistence on using those tried and true sourcing techniques, not to mention standard operating procedure compensation guidelines, in recruiting the scarce KSAOC members of the Metadata Hall team.

Suddenly Zelda hears a disquieting noise. With no one else there, and no obvious explanation for that noise, she begins to search her office and then the corridor outside, while the noise gets louder and more frightening. Not quite the hoot of the night hawk nor the last gargle of the night hawk’s prey, Zelda was hearing the last desperate call of the highly qualified team member candidate who couldn’t get past Creepy’s “I see from your resume that you’ve had three chief architect jobs in the last eight years, and we’re looking for someone who will stay with us forever.” Caught in the act, Creepy had no choice but to try to hire this highly qualified team member candidate, but he wasn’t done applying his consummate incompetence to Project Metadata Hall.

Meanwhile, Doha Doha Castiglione, Dee Dee to his friends, was watching in shock and disbelief the dramatic interaction between Creepy Cummins, whom he’d begun to loath, and Zelda Kahniefmeyer, who had swooped in like an avenging angel to save his candidacy. So, when Zelda suggested that they grab a cup of coffee so that she could tell him more about Project Metadata Hall while Creepy — Mr. Cummins, the head of professional recruitment for the parent company — prepared a proposed offer letter, Dee Dee jumped, literally at the chance. In doing so, he inadvertently knocked over Creepy’s most prized career momento, a picture of him as a young man taken with no less than that paragon of virtue, that role model of effective leadership, none other than Moneybags Drumpf (a very distant relative of you know who!). Apologizing profusely while trying to stand up the beautifully framed and autographed picture and backing out of Creepy’s office at the same time, Dee Dee practically ran after Zelda who was already en route to the cafeteria.

After collecting their beverages and a sweet roll each (for such discussions do benefit from a sugar high), Dee Dee and Zelda sat down in a quiet corner of the cafeteria to get better acquainted. Some preliminary small talk revealed that they had graduated from the same fantastic computer science program at Carnegie Mellon, albeit a decade apart, that they’d studied under some of the same professors, and that they both longed to make the complicated trip to Mount Hagen in Papua New Guinea for the annual August Sing Sing. And while Zelda had to be very circumspect about her next gen architecture project, she did feel comfortable probing (tactfully) Dee Dee’s grasp of object modeling, definitional development and, most important, how to design architectures which could be overhauled completely while in flight. It was a great conversation, with each of them wanting to continue it, and Dee Dee’s antipathy toward Creepy was overtaken by his simpatico with Zelda.

Unfortunately for both Dee Dee and Zelda, not to mention for Great Software, Creepy, left on his own to prepare the proposed offer letter, allowed his essential creepiness to influence his judgment. Thus, he proposed about 80% of the market rate for such a scarce and high demand skill set as a starting salary, thinking that the negotiation that was sure to follow would land them at the market rate rather than his having to deliver above market and/or a signing bonus. Creepy also avoided any mention of incentive pay or equity participation, and added nothing at all to sweeten the deal.

When they returned from their coffee klatch, Dee Dee was shocked and insulted when he read through the draft, and Zelda realized that her whole project, and perhaps career, were being put at risk by Creepy’s creeping. But what can a hiring manager do? And what can a candidate do? Clearly a council of war was needed, but Zelda wanted to collect her thoughts before sitting down to discuss this travesty with Mr. Cummins. So she asked Dee Dee to give them a little time to confer internally on the proposed offer, and Dee Dee agreed to give them forty-eight hours before he needed to respond to another offer that was in hand.

In which we find the first body and meet DCI Fritz

Mr. Cummins and Zelda agreed to meet the next afternoon, just a little after the close of business, because Zelda had to lead a major code review that was going to take all day. That night, in addition to preparing for the code review, she did her homework with Glassdoor, Salary.com, and lots of Google searching to come up with what she thought would be needed in Dee Dee’s offer to attract this highly qualified candidate for a critical position on Zelda’s “bet the farm” next gen architecture project.

Based on her research, she was ready to propose a slightly above market rate salary offer, a substantial signing bonus payable in twenty-four monthly installments, participation in the senior individual contributor incentive compensation plan with goals tied to the success of the next gen architecture project, and a modest but appropriate number of stock options. Zelda also felt that Dee Dee’s work demands would be such that he should have three weeks PTO per year instead of the usual two weeks until his seniority made that the norm.

True to her own nerdy (some would say meticulous) work habits, she prepared a chart of her proposal with the backup included of how she arrived at each line item’s details. Then she rehearsed how she would approach Mr. Cummins and how she would handle each of his likely objections.

The next day’s code review went well, but they were clearly getting behind, not to mention lacking the full brain trust needed to solve specific design challenges, because of the empty position Zelda hoped to fill with Dee Dee. So it was with determination and a real sense of urgency but also the desire to be collegial that she arrived at Mr. Cummins’ office at the appointed time, just after 6:00 PM.

Oddly, Cummins’ office was dark when she arrived. But thinking that Cummins had just stepped away for a moment, Zelda opened the door, turned on the light, and then nearly tripped over Mr. Cummins, lying motionless on the floor, as she walked into the office. Oh no, thought Zelda, he’s had a heart attack.

But, as she looked more closely, she realized that no heart attack could have produced the exotic, beautifully carved paper knife poking out of Cummins’ chest — unless, of course, he had “fallen on his sword” while examining it. “HELPPPPPPPPPPPPPP!” screams Zelda as she uses Cummins’ phone to dial 999. “HELPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP!” screams Zelda, when 999 answers, then pulls herself together to give the 999 operator the details of the emergency — who, what, where, when — along with her own name and contact information. Then, following the 999 operator’s instructions, she walks out of the office, closes the door, and prepares to await the police she’s summoned.

Too exhausted emotionally to stand, she slumps down to the floor, sits with her back against the wall, and tries to collect her thoughts.

It certainly felt like several hours had passed, but in fact it was only twenty minutes before DCI Fritz of the Peterborough CID arrived, followed shortly by his forensics, coroner and crime scene crew (collectively referred to as SOC). After asking Zelda if she would bear with him for a while before he interviewed her, if she’d like a cup of tea and perhaps to wait in the cafeteria, and accepting her thanks for the tea but that she’d wait right there, Fritz began the routine investigation that every sudden death and potential crime scene warranted. Always mindful of the SOC experts doing their preliminary examination of the body in situ, their photographic studies and fingerprinting of the surroundings, their retrieval for detailed analysis of all electronic devices, and so much more, DCI Fritz began his own assessment of the scene.

In which DCI Fritz “partners” with Zelda on the preliminary investigation

DCI Fritz was not a digital native, but he knew from his experience and training how much valuable information could be obtained from the digital, including video, records that surround all of us and from our social media exhaust. His team would take care of probing those sources carefully. But he also knew that, even at the end of 2016, most people still left a fair amount of physical detritus in their wake, from sticky notes inside their tablets with critical passwords to receipts — yes, some transactions still produce paper receipts — in their pockets. And the sudden death of someone, in their own office, inside a tight security building (security which had been tightened even further when Great Software housed their “bet the farm” next gen architecture project there), made a quick and then meticulous search of that office a focus for DCI Fritz.

Doing that quick first look, and remembering that DCI Fritz didn’t yet know who Cummins had been, the nature of his work, etc., two things really stood out. First, there were stacks of carefully labeled manila folders on Cummins’ desk, each with what appeared to be a person’s name on the tab. They were filled with printouts of electronic records, many with handwritten notes and multi-colored tick marks, as well as handwritten records. Second, there was a giant chart on the wall-sized whiteboard across from the desk whose rows were unknown names, whose columns had names which, on first glance, seemed to match those the folders, and whose cells were filled with multi-colored marks whose decoding wasn’t obvious. Taking pictures of the chart on his phone and gathering up the folders once the fingerprint folks had done their thing, Fritz decided it was well past time to speak with Ms. Kahneifmeyer.

Zelda had remained where DCI had found her when he arrived on the scene. As he approached her for his preliminary interview, she appeared to have dozed off (it was nearly 9:00 PM), but in fact she was in the early stages of shock. She’d drunk the sugary tea which was the universal British antidote to shock, but it hadn’t helped much, and she was loath to ask for the Mount Gay with tonic and lime for which the occasion seemed to call.

But Zelda became quite alert looking when Fritz introduced himself and asked for her name etc. As the interview proceeded, Zelda told him of her scheduled meeting with Cummins, of finding the body and calling for help. She explained her role as a project manager and, therefore, as a hiring manager. In response to his questions about the nature of her project, she said that he would need to present any such questions to her boss since her project was in stealth mode.

She then explained that Mr. Cummins, as the parent company’s senior most recruiter, had been assigned to source candidates for her project. Then, once she had made hire decisions, Cummins’ job was to secure their employment via a competitive but within guidelines offer, to sort out any remaining candidate questions or concerns, to arrange a start date, and to oversee the onboarding process — with all of this being done as quickly as possible in order to fill the key positions assigned to Cummins because of his presumed expertise. She also described the events of the previous day which almost lost them a great candidate and then, when she had turned things around as much as possible with that candidate, were further compromised by Mr. Cummins’ proposing an almost insultingly low end job offer.

DCI Fritz took all of this in while quietly assessing Ms. Kahniefmeyer’s demeanor, speech patterns, body language, and all the other clues which he’d learned through experience could signal whether or not the “witness” was being entirely truthful, leaving something out or avoiding some aspect of the situation, going to be a keen and accurate or muddled observer, etc. Ms. Kahniefmeyer was making a very good first impression with no obvious signs of lying, obfuscating, or muddying the waters, but Fritz knew better than to let first impressions solidify before their time.

Once Fritz knew that Cummins was a recruiter, the folders began to make much more sense as did the chart on the wall, but something the “witness” said gave him pause. “I really don’t know why Mr. Cummins would have any such folders or that chart. We’ve automated the hell out of all of our HR processes and data over the last couple of years, really automated all of our administrative and recordkeeping processes. Cummins should be relying on and annotating those automated records, to include records on each job or position against which he’s recruiting, records on each hiring manager and how they like to work as well as their KSAOC preferences, records on each candidate and on every step of the candidate’s passage through the recruitment process, along with summary charts and analytics of everything you could ever want to know.” Zelda had added: “And while I understand that he might want a giant chart so that, at a glance he could see where he is with meeting each hiring manager’s needs, I have absolutely no idea, from the pictures you’ve shown me of his chart and from a quick look at these manila folders, what information is contained in those mysterious, color-coded tick marks.

Since it was now getting on toward 11 PM, and he could see that Ms. Kahneifmeyer was at the end of her tether, DCI Fritz suggested that she leave her car in the office parking lot, and let a policewoman take her home and pick her up again in the morning, about 10:00 AM. He knew he would need her help to decipher those tick marks, which instinct told him were likely to be important to solving this case, so he asked her if she could clear time on her schedule the next day to assist him with this. By now Zelda would have agreed to anything just to get out of there, and so she did.

In which the truly lousy HRM begins to reveal itself

Zelda did not sleep well that night, but she was up early to notify her boss of what had happened and that DCI Fritz would be in touch to request information about her project and, perhaps others on the campus, which she hadn’t been authorized to provide. She also notified her team, without giving them any of the details which DCI Fritz had asked her to hold confidential, that she might be unavailable for most of the day due to an urgent matter that needed her personal attention. By the time DCI Fritz’s team member arrived to drive her back to the office, she was feeling much better after a good night’s sleep, a decent breakfast, and time to collect her thoughts on what had happened.

Back in Cummins’ office, with the body removed and a good bit of rapid cleaning up, Zelda and DCI Fritz sat down with those manila folders and the actual whiteboard in front of them to begin deciphering those color-coded tick marks. With many years of taxonomy building, database design, and pattern recognition and abstraction under her belt, Zelda saw this “project” in those terms and began immediately to note what was known, e.g. she recognized almost all of the row names on the whiteboard as hiring managers across the organizations which Cummins represented as their recruiter for key positions, and she recognized several of the column names, also found on manila folders, as candidates whom either she or one of her colleagues had interviewed. Making the leap from there that all the manila folders might represent candidates and that all the rows on the white board might represent hiring managers, she was ready to tackled the color-coded tick marks.

Realizing that Ms. Kahneifmeyer’s deciphering capabilities far exceeded his own, DCI Fritz left her to get on with it. Meanwhile, he went off to work with his team to digest the scene of crime findings, await and then review the autopsy report, get preliminary findings from the cyber team’s review of Cummins’ electronic devices, from his use of Great Software’s applications through those devices, and his online activity and social exhaust. He also needed to speak with Cummins’ immediate boss, the CHRO Ms. Nikki Patel, and with the head of Great Software’s campus and UK GM, Algernon Wrigley, to whom both Cummins (ultimately via Ms. Patel) and Kahneifmeyer (directly because of the importance of her project) reported. Although he had spoken with Ms. Patel immediately after getting word of the death because otherwise entry might have been delayed at the secured premises and again that morning about the events of last night, he wanted to speak with her in greater depth as soon as she returned later that afternoon from a business trip to Paris. Also, although Cummins wasn’t known to be married or to have any children, Fritz still needed to inform and then interview his next of kin, speak with his banker and his lawyer, and initiate a thorough search of his home. With a very full day’s work ahead of him, DCI Fritz gave Ms. Kahneifmeyer his cell phone number and asked her to call him if she had any progress to report.

Left to her own devices, Zelda did get on with it. First, she went through all of the manila folders, looking at the various combinations of color-coded tick marks and creating a list of each different mark and color combination. Then she did the same for the white board chart. Some of the marks were used quite liberally, in the same and different colors, both on the board and in the folders. Others were used very sparingly, with fewer color combinations. Finally, she found that there were a few marks which only appeared in a single color and which were used quite rarely. And of course, as she already knew, there were no such annotational marks and color combinations offered as a feature of their quite fully featured staffing automation software.

Was Cummins trying to describe something about individual candidates and/or about the interaction of candidates and hiring managers for which their advanced software provided no capabilities? Were there important KSAOCs or other points that Cummins wanted to record in a way which only he could interpret? Hmmm…

In Which The Magnitude Of The Lousy HRM Becomes Clear

With her eyes gone dry and her back aching, Zelda knew she needed a break and some time for all the disparate facts and questions to chase each other around her fertile brain until a useful pattern emerged. Since she was reluctant to go to the cafeteria where gossip about Cummins’ murder was by now swarming, not to mention word of her having found the body, she slipped out quietly, got into her own car which had been left at the office overnight, and drove to the local curry take-away. Then, while parked at the edge of the village pond and eating her curry, Zelda listened to an episode of East Enders and put her Cummins deciphering problem right out of her mind — or so she thought.

When she got back to the office, she found herself taking each of the candidates whom she had interviewed personally and looking hard at their manila folder tick marks and those on the wall chart. All three of those candidates had been well-qualified, but in each case Mr. Cummins had either identified HR-related reasons why they would not be an appropriate hire (e.g. that they did not have the requisite certifications or that a background check showed some unexplained gaps between periods of employment) or reported that the candidate had taken themselves out of the running because of another opportunity. A closer look at those folders showed that all three of those candidates had several tick mark and color combinations in common. So what was it about them that Cummins wanted to remember, that was the same or similar for all of them, but which couldn’t or shouldn’t become a part of their automated record?

Suddenly, Zelda let out a gasp. Those three candidates had all been women of color, one of Indian, one of North African, and one of Caribbean descent. They had all been fairly recent immigrants, either coming to the UK as children with their immigrating parents or arriving for university and staying on. And they were all women of considerable presence, accomplishment, strong ideas, and the effective presentation of those ideas. Could it be that the tick marks were Cummins’ way of recording facts about ethnicity, personality, citizenship, gender, etc. which were NOT acceptable as input to hiring decisions and/or hiring offers?

Then looking at all of the hiring managers on the white board chart who had tick marks against these same candidates’ names, she saw that the intersection cell for each of them with her name had some of the same tick marks in either red or mostly green, whereas the color coding of tick marks on the manila folders never used those two colors. Was it possible that Cummins was recording, by hiring manager, which of these facts about ethnicity, personality, citizenship, gender etc. would be acceptable or not to specific hiring managers?

Knowing that she was on to something, Zelda dialed DCI Fritz’s cell phone and waited impatiently for him to pick up.

In response to Zelda’s excitement over the phone, DCI Fritz stopped only long enough to pick up some tea and scones in the cafeteria, rightly assuming that Zelda hadn’t had anything to eat or drink for many hours, and he was with her within the hour. As she showed him what she had discovered before and since she had called him, he quickly saw the implications.

If Zelda were correct, then Cummins was conducting his hiring practices not only outside of the automated systems intended not only for great efficiency and effectiveness but also to ensure compliance with both regulations and company policies. Clearly Zelda knew nothing about this, but who else might have known or discovered what Cummins was doing?

Was Cummins acting on his own or were there others conspiring to bypass the laws on non-discrimination in employment? If he were acting on his own, could someone have found out and murdered him to protect the company so that, when the story broke, as such stories always do, his death could be passed off as a suicide whilst the balance of his mind was disturbed with guilt? Had Zelda’s unexpected arrival after normal business hours prevented the murderer from finishing the stage management needed to persuade the police that this was a suicide? At this point in their ponderings, they both realized at the same moment that Zelda could well have run into the murderer and herself been killed.

In Which The Question Is Suicide Or Murder

So far, the autopsy findings were inconclusive, and it was just possible that Cummins, in a fit of despair or anxiety over being caught and revealed as a racist, operating on his own as rogue recruiter, had taken his own life in a hari kari sort of way (but hitting his chest instead of his stomach). It could still have been suicide, albeit a weird one as to method and a complete lack, at least so far, of a suicide note, even if Cummins had not been working alone.

And then suddenly a whole raft of other questions surfaced. If there were others involved, how far reaching was the conspiracy and whose careers would go up in smoke if they were discovered to have been a knowing co-conspirator? What Cummins’ was doing was not only illegal but could expose Great Software to very expensive litigation, with potentially large fines, awards, and legal fees, and/or to even more expensive out of court settlements, so were there higher ups who, although perhaps not involved in the original “crime” of institutional discrimination, would see their own careers go up in smoke when this was discovered for their negligence and lack of effective oversight? They could see several possible motives for murder here, along with a growing list of murder suspects if murder it was.

And even if this were genuinely a suicide out of remorse, with no co-conspirators nor avenging higher-ups, was Cummins’ despair the result of new pressures on him to improve his recruiting performance? Had someone found out and been threatening exposure as the basis for a little blackmail? Or had this been going on for long enough that someone had found out and been blackmailing Cummins until the poor man was wiped out, both financially and emotionally?

Stepping back from all of this supposing, and putting aside an entirely personal suicide that had nothing to do with what Zelda had deciphered, DCI Fritz felt is was time to meet with the GM, Algenon Wrigley, and the CHRO, Nikki Patel, together with Ms. Kahneifmeyer. He wanted to bring them up-to-date and to rattle their cages just a little in case either Wrigley or Patel had a hand in this affair. Setting the wheels in motion for a meeting early the next morning, DCI Fritz suggested that they call it a day.

In Which We Meet Mr. Algernon Wrigley And Get Reports-To-Date

As agreed, they all convened in Mr. Wrigley’s office at 7:00 AM, hoping to meet while the building was quiet so as not to attract undue attention. Because she was best qualified to explain their research into Cummins’ recruiting records, Fritz had told both Mr. Wrigley and Ms. Patel that he had invited Ms. Kahneifmeyer to their meeting.

Before the meeting, DCI Fritz had gotten an update on his team’s work, and there was a lot of progress to report. He also wanted to report the results of his own meetings with Cummins’ bank, accountant and lawyer before joining Ms. Kahneifmeyer the previous day. Once everyone was settled, Fritz began his report.

Nothing in Cummins’ finances suggested that he was paying or receiving blackmail nor that he was in anything but reasonable financial shape for a man in his circumstances. His finances, at least as far as they could tell from the obsessively neat office in his modest home, consisted of his salary from Great Software, some income from savings and investments, and a small annuity that he appeared to have inherited. Per his banker, there was no obvious pattern of deposits or withdrawals that would suggestion that he was either the perpetrator or victim of blackmail. So no obvious motivation for suicide there or any indication of a motive if in fact he had been murdered.

Nothing in his legal affairs suggested anything out of the ordinary except that his will left everything he had to a number of charities, at least some of which warranted further investigation. On the surface, they looked reasonable, but one of his team members seemed to recall a connection between one or two of those named charities and some rather unpleasant, anti-immigration agitators. Also, per his accountant, Mr. Cummins was in the habit of making small donations annually to a number of charities which appeared to be fronts for various anti-immigrant, neo-Nazi groups, but here too there was no suggestion of coercion or undue influence.

The further results of the autopsy did show that Mr. Cummins was taking garden variety tranquilizers and may have had a bit more in his system than would be recommended, but not so much as to make him either unaware of what he was doing nor an easy victim for a stranger. The autopsy also showed that the angle of the knife and the damage done by it were not very likely to be the result of a self-inflicted wound.

Summing up their investigations-to-date, DCI Fritz used one of his favorite phrases: “Together with the scene of crime evidence, it’s beginning to look a lot like murder!”

Mr. Wrigley was the first to speak after the word murder had hung in the air for a bit, and he was quite agitated. “But we’re a top security facility, and there’s not a chance that some deranged person from the outside wandered in, weapon in hand, and pushed a knife into Mr. Cummins’ chest,” said Wrigley. “So are you saying that someone here at Great Software, someone we all know, is the likely murderer of our lead recruiter? Stabbing in the chest with a beautifully etched oriental-looking curved knife? Doing this during normal business hours in Cummins’ own office? Without being seen or at least not seen by anyone who has yet come forward? With what possible motive?” By then Mr. Wrigley was sputtering, and he stopped doing so to pull himself together.

Ms. Patel, who had listened to the proceedings in her usual quiet way, taking everything in and thinking carefully about what she had heard, began to speak when Mr. Wrigley stopped for breath. “If it’s an “inside job,” as the Americans say, and no one has yet come forward, either as a witness or with any useful intelligence, then I think we must search for a motive in order to find the culprit unless we assume that this was a random murder by a homicidal maniac who just happens to work here.” And then to DCI Fritz she added: “Have your investigations uncovered any possible motive that’s internal to our organization? Do you have any suspects in mind?” Then, hesitating just long enough for DCI Fritz to notice, Ms. Patel continued: “Could there be something about the work he was doing, about how he was doing it, or with whom he was collaborating that bears on the investigation?”

With this wonderful opening, now turning to Ms. Kahneifmeyer, DCI Fritz said: “Perhaps you’d like to explain our findings-to-date in deciphering Cummins’ manual staffing records?” But before Zelda could respond, Ms. Patel jumped in with: “Manual staffing records? Manual staffing records? What manual staffing records? We converted all of our staffing processes more than a year ago to wonderful new technology from Intergalactic ATS, and everyone’s staffing records are now completely automated.”

Even as she acknowledged her own surprise at finding these remnants, these artifacts, of their previously more manual staffing processes, and using some of the manila folders and Cummins’ white board chart as props, Zelda began to explain what they had found in his office and what their deciphering efforts had thus far revealed. When she got to the part about color-coded tick marks on both candidates and at the intersection of candidates and hiring managers, Ms. Patel, already reeling from the apparent murder of one of her top recruiters, slumped in her chair.

Fearful that Ms. Patel had fainted, Zelda stopped mid-way in her explanation of what she had found and moved quickly to Ms. Patel’s side while DCI Fritz asked one of his officers to bring some water and a cool wet cloth. Mr. Wrigley was strangely silent while the others fussed over Ms. Patel, but in a few minutes her color improved and she asked that Zelda go on with her findings-to-date.

When Zelda had finished, Mr. Wrigley’s sputtering began, slowly and softly at first but then rising to a crescendo of alarm. “How could this have been going on right under our very noses? What about will be the legal and financial fall-out of violating our regulatory and contractual commitments for having fair and open recruiting practices? What will be the damage to our employment brand, short and long term, among our increasingly liberal talent pool of new PhDs. The publicity will kill us if this ever gets out. What could Cummins have been thinking? With whom, if anyone, was he collaborating? And why was he or were they doing this.” As before, Mr. Wrigley’s voice got louder, his speech faster, and he really did seem in danger of some kind of fit. Fortunately, DCI Fritz now had an officer standing by with glasses of water and cool clothes, but Zelda thought to herself that something stronger would be needed before they sorted out this case.

By now her usual self, but as before, Ms. Patel spoke more quietly and thoughtfully. She too realized the huge, negative implications of Zelda’s research on many aspects of the business, and she had many more questions. “How long had this been going on? How many hiring decisions have been made within this biased and, potentially, illegal decision-making framework? Have any of the hiring managers been aware of this? Been complicit? And what about those who had been hired via Ms. Cummins’ discriminatory system? Did they have any idea what was going on? Clearly Ms. Kahneifmeyer didn’t know, but then her project was fairly new, and most of her hires-to-date have been transfers from other parts of the organization.”

In Which Further Investigation Is Planned And They Fear More Victims

So many questions, and very little time in which to track down the answers and determine if they would lead to Mr. Cummins’ killer. Unspoken was the concern that, where one murder had occurred, others might follow.

On one thing they all agreed. Much more deciphering was needed to paint a more complete picture of what Mr. Cummins had been doing, for how long he had been doing it, with what impact on the organization, and with what, if any, co-conspirators. In addition to the deciphering of current files found on Cummins’ desk and the current chart on his office’s white board, much deeper data digging and analysis would be needed to review every candidate who had passed through Cummins’ “hands,” their evaluation process and hired or not hired story, and so much more. And, although records over the past year were automated, digging into earlier records would involve a lot of manual work on files which were stored — as you’d expect — in a records management facility.

DCI Fritz suggested that since the murder had just happened, it was far more likely that it was related to current or recent activities rather than to something which had occurred (or should have but had not occurred) more than a year ago. He also realized that taking Zelda away from her pressing responsibilities on the stealth project were already causing challenges for that project, challenges which would become much worse if she wasn’t able to address them. Therefore, he asked if an analyst could be assigned to work under Ms. Kahneifmeyer’s direction to continue the deciphering and compare what they had learned to the automated records for the current activities.

With information from these files and some interviewing guidance from Ms. Patel or someone on her team, Fritz further suggested that his team could interview every one of the candidates on which they had color-coded, tick-marked, manual records to fill in the demographics and obtain any insight they could as to the hiring process and results. Of course, doing that outreach was going to raise a certain amount of scuttlebutt about what was going on at Great Software, about the murder itself and what connections it might have to the company, so discretion and a suitable “cover story” were needed.

Since it would also be necessary to interview all of the hiring managers who appeared, subject to further deciphering of Cummins’ tick marks, to be either (at least) comfortable or not comfortable with the demographic filtering that Cummins appeared to be doing, Ms. Patel suggested that she was in the best position to speak with each of these hiring managers without raising any unnecessary or distracting fuss. That said, it was going to awkward as hell to determine how best to approach a potentially complicit hiring manager, who might in fact be the murderer, and ask questions which might reveal something useful without appearing to accuse them of anything related to the murder.

Knowing that there was no way to keep a lid on the situation, Mr. Wrigley suggested that he and DCI Fritz hold a joint news conference, announcing that there had been a suspicious death and that an investigation was underway which would involve not only interviewing colleagues of the deceased but also members of the community with whom the deceased had had recent contact in the course of his duties. That would handle both internal and external interviews but not alert unduly the potential culprit(s) to their suspicions of murder by someone connected to whatever scheme or because of whatever scheme Cummins had been running.

With this first news conference behind them, and everyone working hard on their assigned inquiries or analyses, and with the analyst assigned to help her making good progress, Zelda finally had a chance to reflect on all that had happened in such a short period of time. And there was much to consider.

As the person who had found the body and then broken the code which pointed to, if not the motive for the murder then at least the context within which that motive might be found, Zelda found herself almost looking over her shoulder as she went about her project duties. Somewhere there was a murdered whom she probably knew and who did know that it was she who had found the body. There’d been no public mention of coded files or deciphering, no public mention of murder for that matter, but in the small town which is any closed society — and Great Software was exactly that — nothing stayed secret for very long. So Zelda took to parking her car closer to the building, leaving before it got dark, and generally being more cautious than she was naturally. And she also found herself mentally measuring each of the referenced hiring managers for the suit of murderer.

In Which Issues Keeping Popping Up And Being Vanquished

The next big issue to surface — raised by Ms. Patel — was that, with so many important open positions to fill, they couldn’t afford to stop making progress with their recruiting. Someone would need to pick up the open positions for which Mr. Cummins had been the recruiter, really pick up his entire workload, and that would mean either leaving them entirely in the dark about the coded candidates and hiring managers or bringing them into the small circle of Great Software people supporting the police investigation of the murder case. Ms. Patel felt that, with a murderer who had not yet been caught, someone jumping into Cummins’ position might inadvertently expose him or herself to danger if they saw any of the manual files Cummins had kept. And because they didn’t know yet if any other recruiters were using similarly illegal or unethical methods, Ms. Patel was loath to assign an existing Great Software recruiter to Mr. Cummins’ workload.

After conferring with DCI Fritz, but with no one else, they agreed that Ms. Patel would take on recruiting for those key open positions personally and would retain an external contract recruiter to work with her on them. They would use only the electronic files and ATS to manage the sourcing, evaluation and hiring for these key position, and Ms. Patel would say to the relevant hiring managers that she was going to handle this recruiting until the questions surrounding Mr. Cummins’ death had reached closure. It was during this conversation with DCI Fritz that Ms. Patel realized that those same hiring manager were suspects and that her interactions with them could put her at risk. With this realization, Ms. Patel, with a similar sense of caution as that which had enveloped Ms. Kahniefmeyer, began figuratively looking over her shoulder. Meanwhile, DCI Fritz added more officers to the security team monitoring the situation at Great Software’s campus.

The next big issue presented itself to DCI Fritz when he got the final autopsy report with toxicology results. The most interesting item was that Mr. Cummins had a great deal of diazepam, prescribed with care as a muscle relaxant and anti-anxiety medication, in his system at the time of his death. With no obvious muscle pulls or tears, and because it clearly wasn’t the cause of his death, the presence of so much diazepam raised a number of interesting new questions.

Could he have been taking this drug in such large quantities as a matter of routine or had it been slipped to him by the murderer so as to make the murder itself go more smoothly? If it were long term use, was it possible that Mr. Cummins was medicating a guilty conscience? That he’d been doing things illegally and unethically not of his own volition but rather under some form of coercion? Was it possible that Mr. Cummins was not the primary guilty party in this apparent discrimination scheme but rather a pawn being manipulated by someone in higher authority or someone who had some other power over the murdered recruiter? Fritz’s office was already in touch with Cummins’ GP, and they’d know soon enough if diazepam were being prescribed and for what? But even if Cummins was taking this medication under his BP’s instructions, there were no allowed uses that would explain such a large quantity being present in the autopsy.

At this point in the investigation, DCI Fritz thought that there were too many questions rolling around in his head. And with new information coming in from his own team’s interviews with the tick-marked candidates, the continued deciphering under Ms. Kahneifmeyer’s watchful eye, and Ms. Patel’s preliminary meeting with each of the hiring managers who had key positions which needed filling urgently, DCI Fritz thought a meeting with the two ladies, informal and quiet, might be a good idea. So he suggested that they meet for lunch at the type of tea shop where their colleagues weren’t likely to turn up.

In Which DCI Fritz Enlists Zelda And Ms. Patel As His “Partners”

When they’d gathered, making small talk until their food had been served, it struck each of the two ladies, without any conversation about it, that they weren’t being treated as suspects but rather as partners — or perhaps just assistants — in the investigation. And while they both wondered about this privately, neither gave voice to their impressions. Meanwhile, once they were settled and enjoying their excellent lunch, the serious discussions began.

DCI Fritz first reported on the autopsy and toxicology results, calling attention to the high levels of diazepam found in the victim’s system. He’d heard back from Cummins’ GP, just before he’d met the ladies for lunch, who was shocked that Cummins was taking this controlled drug. It had certainly not been prescribed by him, and NHS records showed no such prescription over the last five years (as far back as he had looked).