Anthony Bourdain’s suicide and all the related tributes, personal introspections, lamentations and analysis have really upset me, and not because I feel his loss personally. Not being a foodie, I didn’t even know who he was until I caught a piece of one of his shows because I saw it mentioned as including Barack Obama. But the manner of his death, by his own hand, coming as such a total shock to people, the unexpected suicide of someone so full of life whose private demons weren’t even that private, has shaken me — and many others if I can judge by a recent private discussion thread of which I’m a member. But what has really shaken me is the memory of the first suicide I experienced, more than a half century ago, of a much loved friend, Joey Shapiro.

I fell in young love with Joey at first sight at a Jewish youth group gathering in my early teens. He wasn’t just gorgeous on the outside — and I mean absolutely gorgeous — but he was also gorgeous on the inside. He was very kind to the geeky, not particularly ornamental girl I was (and remain) at a time when being geeky and non-ornamental were the kiss of death for ever being kissed. I had always had lots of guy friends, and I never missed a social event for lack of a date, but there just wasn’t anything about me then which aroused the ardor of young men. And although I’d long since accepted the fact that I would star as a student rather than as a social butterfly, it still hurt that the yardstick against which girls were being measured was one against which I could never measure up. And then Joey came into my life, and for the first time ever I experienced something more than friendship from a boy my own age.

All through high school, even as I dated other young men and gradually gained confidence in my social graces, Joey was never far from my thoughts. But he lived in another town, more than a half hour’s drive from my home at a time when few of us had cars or were allowed to borrow our parent’s car for so long a journey. So I only saw him at occasional Jewish youth group gatherings or when one of the girls I had met in the same way invited me to a sleepover weekend much closer to where he lived. We kept in touch via occasional letters and cards over which I’m sure he labored as much as I did to strike just the right tone. And we had even less frequent phone calls because a long distance call was a MAJOR expense reserved for only the most important communications. We never spoke of the other people we were dating or even much about our day-to-day lives but focused instead on how we were feeling and on our dreams for the future

Joey was going to be a doctor, and I was going to be a nuclear physicist. Neither one of us had any idea of the challenges we would face to realize those dreams. Joey wasn’t as gifted a student as I was, but I had never thought about that since, living so far apart, my all As and his mostly Bs along with our widely divergent SAT scores, never entered our conversation. I loved looking at him, talking with him, feeling special because of his attention, and I learned that he loved my snappy patter and admired my very different ambitions from most of the girls we knew. I didn’t realize until we began applying to and getting admissions decisions from colleges that he would not be going to an obvious feeder college for medical school, and I had no idea of just how difficult it was to become a doctor, let alone a nuclear physicist.

By the time we entered college, I was imprinted romantically on someone else, but Joey still held a special place in my heart, and we continued to keep in touch in small and infrequent but very important to me doses. His field reports were always upbeat even as mine were increasingly self aware about the fact that I lacked the spark of genius which is needed to become more than a garden variety physicist, about the realities of working my way through Penn, and about my struggles to re-imagine my future. There were no social media to enable easy, quick, cost free interactions; every exchange took time to write a note, stamp and mail it and then a lot more time to reach its destination and even more time before you could expect a response, by which time the moment had so moved on that you didn’t even remember what you had written in the first place. Needless to say, neither of us had the money for many now much longer distance phone calls.

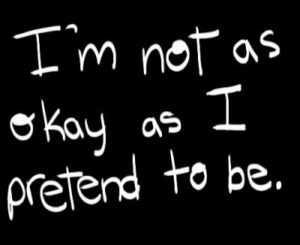

Once I got to Penn, I rarely went home except for very short vacations. I often stayed at Penn in the summer, e.g. after my freshman year I worked at the post office on the night shift, took some classes and ran my typing service. If truth be told, going home to the problems I had left behind wasn’t an attractive option, and I really needed to make as much money as possible each summer to pay my expenses for the next year. I don’t remember how Joey spent his summers; our communications had become fewer and further between as my life, especially my romantic life, had become more complicated. But one note I received should have given me pause, should have alerted me that something was very wrong, but it didn’t. Everyone’s surprise at Anthony Bourdain’s suicide mirrors my own disbelief over Joey’s suicide — and it shouldn’t have because I shouldn’t have been surprised.

Joey’s ended his life one college break summer, and I never saw it coming. Yes, I knew from my own experiences in organic chemistry, that pacing course whose grade had to be tops for med school entry, that he would have struggled with it. And that last note I received, in which he let slip a little of the charismatic, always upbeat public persona, might have warned someone more in touch with him day-to-day. But that so young, so unfinished Naomi really didn’t see it coming, let alone the means he would choose to end his life.

Suicide is not only a terrible tragedy, but it is also a terrible sin in the orthodox Judaism of my youth. I begged my parents to let me attend his funeral, but of course they wouldn’t hear of it, and neither would they attend on my behalf. They did pay a condolence call to Joey’s grieving parents, whom they and I had never met, parents so destroyed by the manner of his death that they returned my own letter of condolence. I thought then that I should have known, that there should have been something I could do to prevent this tragedy, that I had become so absorbed in the challenges of my own life after my dream of becoming a nuclear physicist hit the hard reality of my limited intellect, that I had violated the most important principle of friendship — being there.

It’s been a very long time since Joey Shapiro took his life, and I would never have written this while his parents or brother were still alive. But today is the right time to remind myself and everyone reading this post that we must be vigilant, we must be alert to the challenges that our friends and family members are facing, we must engage with them beyond the superficial “how are you” “I’m fine” which passes for connecting now, we must be there for them. In my head I know that there’s very little I could have done to save Joey even if I had known that he might commit suicide. I wasn’t one of his closest friends nor a family member. Most important, I was too young to understand what he was going through and too resilient and full of hope myself to comprehend the lack of resilience and tendency toward despair which are present in many suicides. But in my heart, I grieve for Joey and for my failure as a friend, and it’s a grief that’s come at me full tilt in the wake of Anthony Bourdain’s suicide.