I spent a very intense week last July in Silicon Valley meeting mostly full days each with Workday, SuccessFactors, Taleo, Saba and SAP, and would like to start this post with a huge and very public thank you to all of these vendors for their time, their preparations, and their hospitality. I’ve also been doing many vendor briefings and deep product dives this year (see here, here, here and here for those observations) , and those vendors also deserve a big thank you for their time and prep.

But in spite of these previous posts, and perhaps because all we’ve heard this year is debt ceiling, national debt and deficit spending, I’ve been thinking a lot about our own industry’s technical debt. Now it’s time to surface this important and complex issue. And if you think this is only of interest to techies, please think again. What end-users don’t know about what lurks in the corners of their software definitely hurts them.

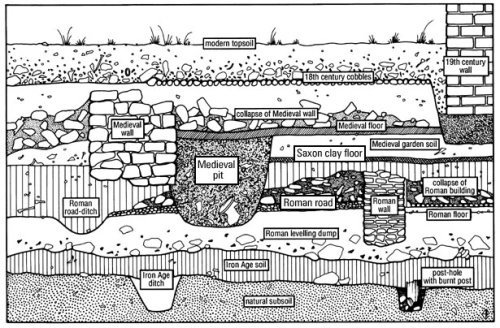

Technical debt, which comes in both a design and a code flavor, is the build-up of outdated designs, badly written code, object model short-comings (or never-comings for those vendors whose products were designed around either the data models of an earlier era or, heaven-forbid, without formal models at all), architectural flaws, lack of support for newer delivery devices and modes, and more. This is the build-up of flaws or simply outdated work that many to most software vendors accumulate as they progress from initial product concepts through product delivery and, hopefully, through ever more product releases if they are reasonably successful. It’s the sludge at the bottom of your vendor’s software “tank,” and it’s creates a considerable drag on vendor profitability, speed to market for new functionality, operational stability and error-free updates, etc. And buyers are paying for all of this with their licenses/subscriptions/maintenance, not to mention their manual work-arounds, customizations, add-ons, duplicate systems, disengaged workforces, impossible to change business rules, etc.

Great vendors are constantly paying off this debt through ongoing refactoring and redesign of their current software. When needed, and often in parallel, these same great vendors (but they are the minority) completely rethink, re-architect, and rebuild their products, thereby launching their own next generation. But many vendors don’t do nearly enough to pay off this debt. They prefer to invest in new features, new technologies, marketing and sales — in things buyers and investors can see. And who can blame them when many market influencers/analysts, let alone buyers, rarely mention or even understand what’s under the covers.

Eventually, vendors who don’t pay off their technical debt, who don’t pay it down very deliberately and aggressively, build up so much technical debt, especially design debt, that they drown in it. There has almost always been a buyer for these technical debt-laden products/companies, often a buyer that can squeeze a little more return on their bargain price investment and/or one with the capability of rejuvenating the product itself. But even a little such debt can turn a very successful vendor into a vendor of legacy products right before the eyes of their unsuspecting customers.

For customers, the amount of technical debt lurking under the covers of your seemingly shiny new software has a major impact on whether or not you achieve the very benefits for which you’ve committed resources to this vendor and to the implementation of this software. The more debt, the less likely you are to get those benefits now and into the future, and the less likely your vendor partner is to maintain what may be at this point a very successful track record. The accumulation of technical debt is one reason why being a late adopter isn’t always the wisest move because you get all the burden of this debt without having enjoyed the period of innovation before that burden became so great.

Even more important from a customer perspective is the drag on your vendor’s ability to continue to innovate, to deliver promised and much-needed functionality, and to continue to do so at an acceptable price. Technical debt raises vendor costs, reduces quality, and extends time to market to do even simple enhancements. And we all know that today’s business environment requires us to change our HRM practices quickly and with confidence that our HRM software won’t buckle under the load or cause us to spend money we don’t have on those awful workarounds, add-ons, and side systems.

One amazing (at least to me) culprit (but by no means the only one) in the creation of all this HRM software technical design debt is the extent to which that oh so successful PeopleSoft HRMS has influenced a generation (two generations?) of industry architects and business analysts. PeopleSoft was designed for a different era of HRM, for an era in which the contingent workforce wasn’t central to workforce planning and productivity, in which KSAOCs were only marginally understood and KSAOC-centric HRM was in its infancy, in which far fewer organizations were truly global, and the list goes on. PeopleSoft didn’t require the granularity of positions and many to most PeopleSoft implementations relied on an everything but the kitchen sink job code table to drive its business rules. Worse yet, the early design of PeopleSoft drew upon the team’s knowledge of a still earlier era’s mainframe HRMSs, and there was no foundational domain modeling done to rethink HRM in the early days of PeopleSoft. I could add that PeopleCode wasn’t meta-data driven, that it wasn’t effective-dated at its core, and that the North American payroll wasn’t a payroll engine but a very traditional (COBOL?) zero-to-gross and gross-to-net application. And don’t even get me started on external trees to compensate for the lack of a generalized treatment of recursion, e.g. in organizational structures. Shall I go on?

When PeopleSoft came to market, it made its competitors look dated and frumpy, it gave configuration power to HR folks that they’d never had before, and its marketing and sales were superb. But when I see key design principles from PeopleSoft, which should have long since been put out to pasture, perpetuated in shiny new 2011 software, I AM NOT IMPRESSED. So you can imagine my reaction when looking under the covers of various talent management applications this year only to discover that the everything but but the kitchen sink job code structure has been reincarnated more than once without a proper treatment of the essential and entirely separate concept of position, that many of these new applications are not systemically effective-dated (their data may be but the applications themselves are not), that there still isn’t proper handling of the contingent workforce, and that they haven’t really addressed the long understood problem of handling the many recursive objects in our domain with a suitably generalized approach. Arghhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh.

PeopleSoft was in fact a major and important technology upgrade of much older functional thinking, and it was a wild success in an era when everything around it was still tied to the mainframe. That success has continued, and there have been lots of improvements to its design and its code base over the years. But there remain many business analysts in our industry who couldn’t explain the role that job versus position play in the HRM object model and HRM processes to save their lives, and some of this ignorance can be traced to the long influence tail of PeopleSoft. I could go on, but I think you get the picture. And if you’re an HR leader considering the acquisition of new software, the last thing you want is yesteryear’s thinking and design in a new package.

So, no matter how slick a specific vendor’s mobile/social/global/gamified/etc. demo looks, you’d better start poking under the covers to see how much and what kind of technical debt, especially design debt but that code debt matters too, your prospective vendor is dragging around. To detect the presence of potentially harmful technical debt in HRM software, and here I’m speaking of design rather than the coding debt, which is much harder to detect, here are some important and easily observed/ferreted out clues:

- Is their so-called modern software built upon a contemporary object model? You should be very afraid if your vendor wouldn’t know an object model if they tripped over one. Just ask them for a high level walk-through of their major HRM object classes and how they are related, making sure that you have someone in the room on your side who really knows object models and, in particular, the HRM object model. If all they can come up with are entity-relationship diagrams and the physical design of their relational database tables, then you may well be looking at very old think software design in a shiny new package. And if they do come up with a great-looking object model, use some of my “killer” scenarios (just search my blog on the phrase “killer” scenarios to find them) to test it.

- Is their so-called modern software systemically effective-dated? This is really easy to detect using a good chunk of my “killer” scenarios on this subject.

- Are all the business rules that drive their so-called modern software abstracted to effective-dated meta-data (or to effective-dated object attributes and methods which can be manipulated on the fly?)? Can their meta-data be configured non-destructively (so without impacting the push of future releases)? Are there any business rules expressed as application code — a horrible No No in modern software?

Since all vendors who’ve been in business for more than a few years will certainly have some technical debt, not only should you assess the extent of same but you should also pay attention to when/how/at what pace/with what resources/with what executive commitment your vendor is working to retire that debt. Software ages, it really does, and it takes ongoing investment to slow the aging process.

But eventually, no matter how much good work is done to pay down that technical debt, the pace of technology and business change really does force us to stop, take out that “blank sheet of paper,” and make a leap. Some established HRM software vendors may get that done, but most won’t. It’s VERY hard to convince senior management of the necessity and then to sustain their support during the tough years when there’s little to show for that next gen effort. But those established vendors who can take their customers forward, who are willing to bet it all on that next gen and not bury their (and their customer’s) futures in technical design debt (even if the code is new) to maintain “backward compatibility,” are vendors deserving of our collective respect.

For more information on technical debt and related topics, here are two very useful blogs. The wonderful graphic above is from the first of these. http://observationsonerp.blogspot.com/2009/03/hidden-architecture-syndrome-definition.html http://www.andrejkoelewijn.com/wp/2010/11/25/lac2010-technical-debt/